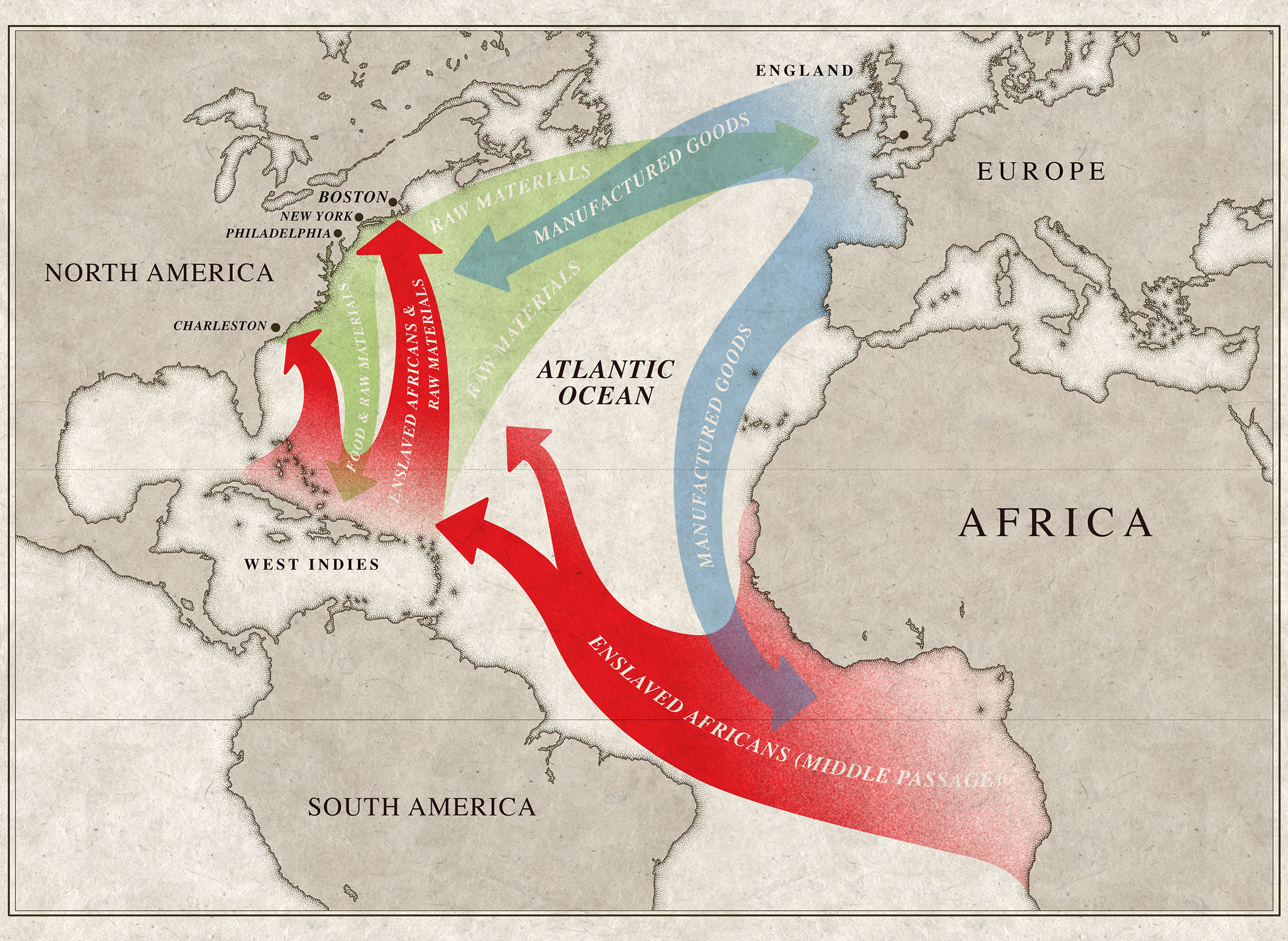

When many people think of the slave trade, they picture ships crossing the Atlantic—the Middle Passage that carried millions of Africans to the Americas. But after the U.S. banned the international importation of enslaved people in 1808, another massive migration unfolded within American borders. This movement, known as the Second Middle Passage, uprooted and displaced more than one million enslaved African Americans in the 19th century. For genealogists, it represents one of the most challenging yet crucial eras to research.

What Was the Second Middle Passage?

The Second Middle Passage refers to the domestic slave trade within the United States, spanning roughly from 1808 until the Civil War. Enslaved men, women, and children were sold from the Upper South—states like Virginia, Maryland, and Kentucky—to the Deep South, where the booming cotton economy demanded more labor.

This was not a single journey across the ocean but a series of forced migrations by ship, wagon, rail, and on foot. Entire families were broken apart as traders sold individuals to distant markets in New Orleans, Natchez, or Mobile.

The Scale of the Migration

- Over 1 million enslaved people were relocated during this period.

- New Orleans became one of the busiest slave markets in the world.

- Some were moved by ship along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, recorded in manifests that listed names, ages, and physical descriptions.

- Others traveled overland in chained groups known as “coffles,” marching hundreds of miles southward.

For genealogists, this explains why ancestors who appear in Virginia records of the early 1800s may suddenly reappear in Louisiana or Mississippi decades later.

Genealogical Clues in the Records

Records from the Second Middle Passage can help researchers trace enslaved ancestors. Sources include:

- Domestic slave trade manifests – Required by law for coastwise voyages, often listing first names, ages, and descriptions.

- Bills of sale and auction records – Transactions in local courthouses or newspapers that document individuals.

- Estate inventories and probate records – Enslaved people were considered property and thus listed by name in wills and inventories.

- Plantation records – Journals, ledgers, and account books sometimes recorded labor assignments and family groupings.

- Census slave schedules (1850, 1860) – While they rarely list names, they provide age, gender, and owner, which can be cross-referenced.

The Human Cost

Each record reflects an immense personal tragedy. Children were sold away from parents, husbands from wives, siblings from siblings. Families were torn apart on a scale so large that many African American genealogists encounter abrupt gaps in ancestral lines during this period.

Why It Matters

For descendants of enslaved people, reconstructing these migrations is an act of resilience. Each identified name in a manifest or estate record reclaims a life once reduced to property. Each connection across regions—linking Virginia roots to Mississippi fields, or Maryland families to Louisiana plantations—restores continuity where history tried to erase it.

By studying the Second Middle Passage, genealogists help transform a narrative of loss into one of remembrance, ensuring that those who endured forced migration are not forgotten.

The Second Middle Passage was one of the largest migrations in U.S. history, though it is often overshadowed by the transatlantic trade. For genealogists, it provides a framework for understanding why family lines stretch from the Chesapeake to the Mississippi Delta. More importantly, it offers a pathway to honor the endurance of those who survived and the legacy they passed down.